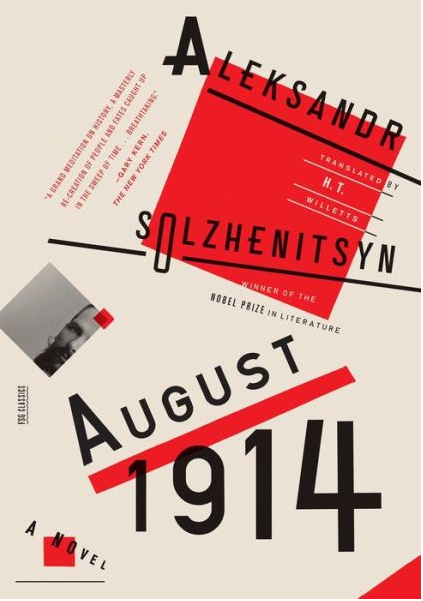

The Red Wheel > Node I: August 1914

Node I: August 1914

August 1914 is the first and best known of the four Nodes that constitute The Red Wheel. By concentrating on a couple of crucial weeks at the beginning of the First World War, Solzhenitsyn highlights the underlying sclerosis and vulnerability of a Russian old regime whose stability was erroneously taken for granted by revolutionaries and reactionaries alike. In fact, the regime’s ignorance and incompetence reared its head at the Battle of Tannenberg in East Prussia, a great military confrontation between the Russian 1st and 2nd armies and the German 8th Army that took place between August 17 and September 1, 1914. Tannenberg was a catastrophic defeat—over a hundred thousand Russian troops were killed or captured—that was a portent of disasters to come. Much of August 1914 is dedicated to describing the mistakes, misjudgments, and false assumptions that culminated in Russian defeat at Tannenberg. These mistakes even included the failure to encrypt messages that were sent to commanders on the front!

The commander of the Russian 2nd Army, General Aleksandr Samsonov, is in important respects an admirable figure: he is decent, pious, and imbued with a deep and abiding love of “mother Russia”. He embodies the best of old Russia but not a few of its vices as well. Influenced by the “spiritualism” of Tolstoy and by an excessively “fatalistic” confidence in Providence that borders on superstition—he was finally incapable of providing clear and effective leadership. He lacked the imagination to act decisively, to transform situations through his own initiatives. The suicide in the forests of East Prussia of this faithful and tragic figure provides an opportunity for shameless self-exculpation on the part of a military and political class that refuses to take responsibility for the mistakes that led to the disaster at Tannenberg.

This collective abdication of responsibility leads to one of the most dramatic confrontations in the work as a whole. Colonel Vorotyntsev, in the presence of the Supreme commander of the Russia’s Imperial forces, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, takes the leaders of Russia’s armed forces to task for their vicious scapegoating of General Samsonov and for their criminal refusal to come to terms with the generalized corruption and incompetence of the regime. For this act of courage, Vororotynstev is posted to an isolated front where he does his duty for the duration of a war the wisdom of which he does not hesitate to question.

In eight remarkable chapters of August 1914 (the so-called Stolypin cycle), Solzhenitsyn painted a portrait of the statesman Pyotr Stolypin, scourge of the revolutionary left and reactionary right alike and the last best hope for Russia’s salvation. Prime Minister of Russia from 1906 until 1911, Stolypin’s abiding concern was to promote far-reaching agrarian reforms that would lead to the creation of a “solid class of peasant proprietors” in Russia. He believed that a property-owning peasantry would provide the social basis for a revitalized monarchy in Russia. He was a “liberal conservative” who rejected pan-Slavist delusions and who advocated a monarchy that respected the rule of law, one that could govern in cooperation with a “society” that had an increasing stake in the existing social order. But Stolypin was shot (in the presence of the Tsar) at the Kiev opera house in September 1911. His assassin was, quite strikingly, a double agent of the secret police and revolutionary terrorists.

– by Edward E. Ericson, Jr. and Daniel J. Mahoney, The Solzhenitsyn Reader